Young People Don’t Need a Degree to Fight for Their Future

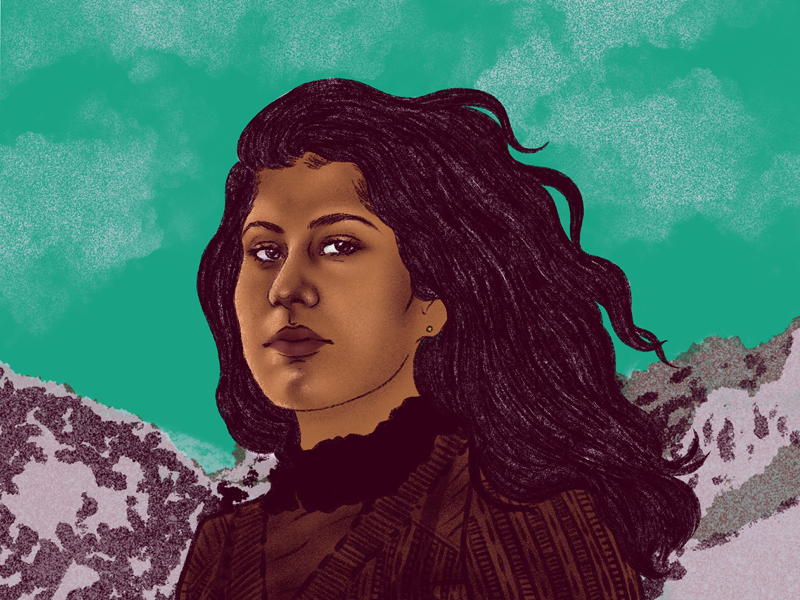

Youth climate activist Mishka Banuri describes how she pushed past her fears of imposter syndrome to join the climate fight and calls on young people everywhere to demand bold solutions to the climate crisis.

This page was published 3 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

Mishka Banuri is a 19-year-old climate activist and the co-founder of Utah Youth Environmental Solutions (UYES), an organization that empowers youth to hold government officials accountable in combating the climate crisis. In 2018, Banuri and UYES led the effort to pass a resolution in the conservative Utah legislature that formally recognized the validity and existential threat of climate change.

There’s a reason why young people are among the most vocal advocates for bold solutions to the climate crisis: It is our future at stake. Unless we make clear to our leaders that this is an emergency threatening every aspect of our lives, they won’t listen.

I credit my awakening as an environmental activist to a high school camping trip to Bears Ears, an iconic natural landmark in Utah composed of juniper forests, buttes, and canyons. For years, the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition, a group of Indigenous nations, had been urging then-President Obama to designate the site as a national monument. While at Bears Ears, I learned about the Indigenous tribes who once called this site home, and whose detailed handprints engraved on the rocks told the stories of their cultural traditions and deep connections to the natural world. My heart broke after hearing about the Indigenous genocide at the hands of European colonizers, and how the few remaining tribes were fighting to hold on to the land they rightfully owned. It was here that I understood the meaning of environmental racism and how it is deeply intertwined in both American history and the climate crisis.

This experience eventually led me to help organize the Utah People’s Climate March in 2017. At first, I felt incredibly nervous to join in. I had major imposter syndrome — doubting that I could contribute something of value to this group since I was just a high school student. I didn’t even have a specific skill set, like event planning or media experience. But I eventually built up my courage, and slowly, my self-doubt turned to excitement. The march organizers were incredibly welcoming and created space for me. They allowed me to explore and learn about community building, grassroots activism, and the importance of fostering an inclusive movement that represents overlapping struggles and life experiences.

This emphasis on intersectionality particularly resonated with me as a Pakistani American Muslim. Growing up, I read many stories in the Quran that illustrated how all aspects of humanity and the natural world are inherently connected, and that when we pollute the earth, we are essentially polluting ourselves. During the climate march, the speakers acknowledged how the climate movement was not only seeking a solution to the climate crisis, but also an equitable and just future where true liberation is achieved. This means ensuring that we advocate for justice across all aspects of our collective identities, from racial justice to migrant justice to reproductive justice. To me, liberation is synonymous with autonomy: having the ability to choose how to use our bodies and minds, to be able to breathe clean air and to drink clean water.

The organizers of the march taught me how to establish a lasting movement from one specific event, building upon that momentum through subsequent actions that bring people together and strengthen the core mission. While the march was a one-time display of collective solidarity, the organizers ensured their message continued to spread long after the march was over. I asked myself how I would amplify their efforts, and I began to research local climate advocacy organizations.

Almost a third of Utah’s population is under 18 (the national average is only 23 percent). Young people overwhelmingly support progressive climate action, and if given the opportunity, I knew we could have an immensely powerful impact on pushing our (generally more conservative) legislators to take bold action on this crisis.

In the four years since UYES began, we’ve grown immensely and have established a reputation as an effective, unrelenting advocate for bold climate action. We’ve kept our leaders accountable despite encountering incredible adversity.

In 2018, we convinced our legislators to pass a state resolution that formally acknowledged the threat of climate change. We did this by organizing an independent hearing and filling it with a room full of young people to talk about why urgent climate action is needed. My peers also called their representatives’ offices nonstop, to the point at which one representative said that he’d vote to support the resolution as long as the calls to his office would end.

When confronted about climate change inaction, politicians and lawmakers will often tell me what they think I want to hear: “Your passion is so inspiring. You should go to college, then run for office and do this work.”

But the reality is that we don’t have the time to wait any longer to solve this crisis, and young people don’t need a degree to be qualified to fight for their future.

Interview conducted and edited by Bala Sivaraman and Jaida Nabayan.

Mishka Banuri is a 19-year-old climate activist and the co-founder of Utah Youth Environmental Solutions (UYES).

Earthjustice’s Washington, D.C., office works at the federal level to prevent air and water pollution, combat climate change, and protect natural areas. We also work with communities in the Mid-Atlantic region and elsewhere to address severe local environmental health problems, including exposures to dangerous air contaminants in toxic hot spots, sewage backups and overflows, chemical disasters, and contamination of drinking water. The D.C. office has been in operation since 1978.